Wilde slowly gained a reputation that spread beyond the student body to a few of the professors. A Balliol College don described him as “a brilliantly clever scholar, who had strangely good taste in art and in humanity.” When it came to clothes and grooming, however, he wasn’t quite so tasteful. “He never looked well-dressed; he looked ‘dressed up,’” an acquaintance noted. The 1875 Oxford and Cambridge Undergraduate’s Journal satirized him as the outlandishly-dressed aesthete O’Flighty (a play on O’Flahertie, his unambiguously Irish middle name) and poked fun at his garish clothes and uncombed hair.

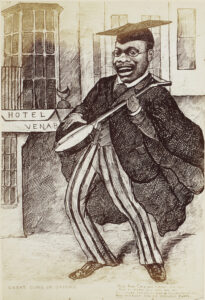

While Wilde preened within Magdalen’s golden walls, Cole sought public audiences by giving speeches at the Oxford Union. He was determined, ambitious and exceptionally brilliant. To save money, he didn’t immediately join a college and worked throughout his degree to supplement his income, giving music lessons and tutoring candidates for their first BA examination. Whatever disadvantages he faced, Cole showed what he was made of by gaining a degree in “Greats”, Oxford’s blue-ribbon subject. After obtaining his degree in 1876, Cole officially became a member of University College; to win a place here was a coup (Cecil Rhodes, the imperialist who was making his fortune in South African diamond mines, had been refused by the college only a few years earlier).

T. Shrimpton, ‘Old King Cole’ from 1224 caricatures of Oxford life, G.A. Oxon 4o 414, fol. 533.

Reproduced by kind permission of The Bodleian Libraries, The University of Oxford.

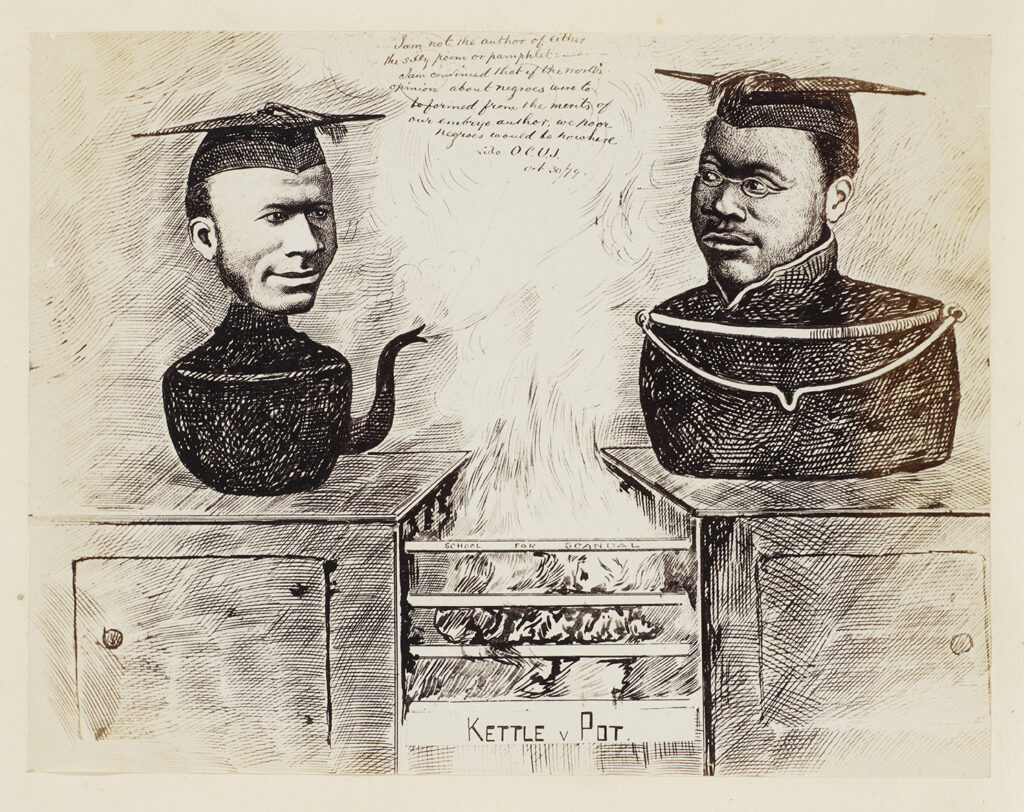

In the autumn of 1876, another Black Sierra Leonean, Joseph Renner Maxwell (1857-1901), came up to Oxford to become a student at Merton College. Like Cole, Maxwell debated at the Oxford Union. A contemporary racist caricature titled “Kettle v Pot” depicts them discussing Cole’s anti-imperialist publications.

Unlike Cole, Maxwell thought his Oxford experience a positive one. “I was not once subjected to the slightest ridicule or insult, on account of my colour or race, from any one of my fellow students,” he said. Maxwell later experienced racial exclusion when he applied to the Colonial Office. Even with a law degree from Oxford, he found himself shut out of government service.

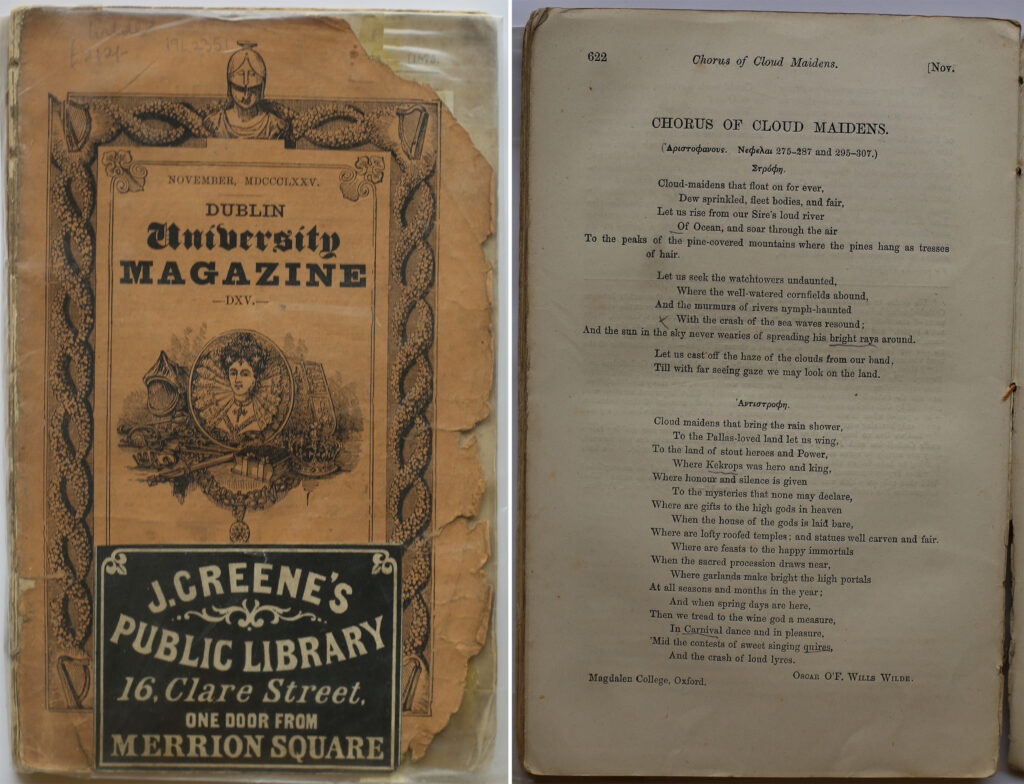

In his first term, Wilde translated into a poem Aristophanes’s satire of sophistry and social aspiration and published it in Dublin University Magazine. “Chorus of Cloud-Maidens” became his first publication. Though he placed it in an Irish periodical, he signed the poem from “Magdalen College, Oxford” to indicate his new cultural cachet. Although he wanted to be English, he had no wish not to be Irish. Shrewdly, he chose to be both.

O. Wilde, ‘From Spring days to Winter’ in Dublin University Magazine, 515 (November 1875). Magdalen College Library Magd.Wilde-O. (DUB) no.515

“From Spring Days to Winter,” the second poem Wilde published, told of springtime love. In the warmer months of 1876, when he was 22, Wilde’s affections blossomed once again. He gushed to his friend William Ward about his first sweetheart, the “exquisitely pretty” grey-eyed Florence Balcombe (later Mrs. Bram Stoker). She was “just seventeen with the most perfectly beautiful face I ever saw,” Wilde said.

Photograph of Oscar Wilde, Florence Ward (centre), Gertrude Ward and an unidentified gentleman by Jules Guggenheim, 1876. Magdalen College Archives Acc99/62

That summer, William’s two sisters visited him in Oxford, and Wilde became infatuated with Gertrude Ward. You can see photos of that visit exhibited here. This is the first time that these photographs of Wilde have been shown publicly. After spending a few days in Wilde’s company, the younger sister, Florence, confessed her true feelings about him to her diary, which is exhibited here. The diary gives us a privileged insight into Wilde’s flirtatious nature and his attempts to charm young women. The perceptive seventeen year old Florence saw Oscar jostle his way to her sister’s side whenever possible. She thought Oscar and Gertrude’s romance terribly silly.

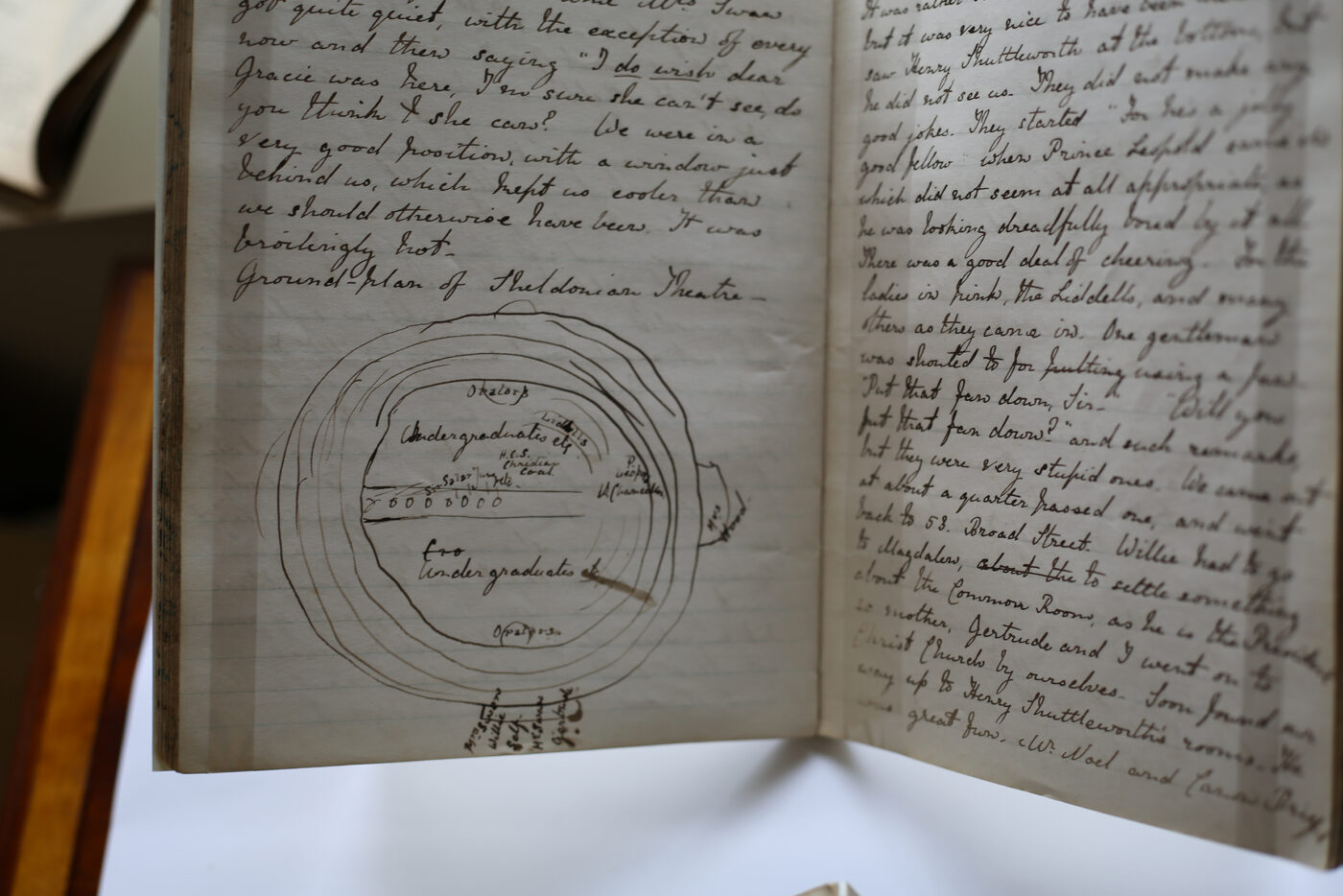

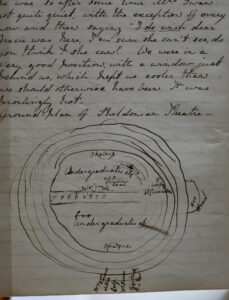

Anna Florence Ward’s Diary , 1876. From Florence’s point of view on the Sheldonian’s outermost rim, she could see all the undergraduates, as well as Prince Leopold and the Liddells of Christ Church, whose daughter, Alice, was the inspiration for Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. To Florence, all of them seemed to orbit Cole. Magdalen College Archive MS 618

Besides, there were other Oxford students who fascinated Florence. On a warm June evening, she was strolling near Christ Church College, hoping to catch a glimpse of Prince Leopold, a student of the College. Instead, she saw another student whose fame rivalled the Prince’s. “Saw Christian Cole (Coal?) also (the nigger),” she scribbled in her diary that night.

Three days later, Florence went to Commemoration, the annual celebration of the University’s founders and benefactors. When Cole entered the Sheldonian Theatre, hundreds of eyes turned to him.

Florence took the scene in. From the sketch she made of it in her diary, the circular, concentric rows of seats looked like a galactic map of the great and the good. At its centre, there was one dark star around whom the rest orbited. She labelled that star “Christian Coal.” You can see her sketch exhibited above.

Later, Florence returned to Magdalen’s cloisters to have her photograph taken with the students. She posed in the centre of the group while Wilde, dressed in a sober dark suit and bowler hat, hovered on the periphery.

Group photograph including Oscar Wilde (front centre, in hat), Gertrude Ward (to Wilde’s right), the diarist Florence Ward and others by Jules Guggenheim, 1876. Magdalen College Archives Acc99/62

Of all the figures mentioned here – Cole, Maxwell, Harley, Locke, Wilde – Florence Ward was no doubt the most excluded from Oxford. On the basis of her sex, she could never have been a member of the University in 1876. Instead, she became a suffragette. Alongside the suffragette leader Emmeline Pankhurst and 125 other women, in 1912 Florence Ward was sentenced to four months in prison for criminal damage.

The first women’s Colleges were founded too late for Florence: Lady Margaret Hall and Somerville opened in 1879, followed by St Hugh’s in 1886 and St Hilda’s in 1893. From the late 1870s, women could attend lectures and sit exams but they were denied the right to receive the degree to which, had they been men, they would have been entitled. In the video below, Prof. Nicholas Shrimpton reflects on his experience of being a tutor at Lady Margaret Hall, a former women’s college, and compares it to his experience of being a student at the all male Balliol College:

It was not until 1920 that women became full members of the University and were allowed to graduate. It was not until 2016 that a woman became Vice Chancellor of Oxford University. Professor Louise Richardson who, like Wilde, is an Irish graduate of Trinity College Dublin, was the first woman to hold the position. “Hiding our history is not the route to enlightenment,” Richardson told the BBC in 2020. “This university has been around for 900 years. For 800 of those years the people who ran the university didn’t think women were worthy of an education.” In 2020, the university celebrated 100 years of co-education.

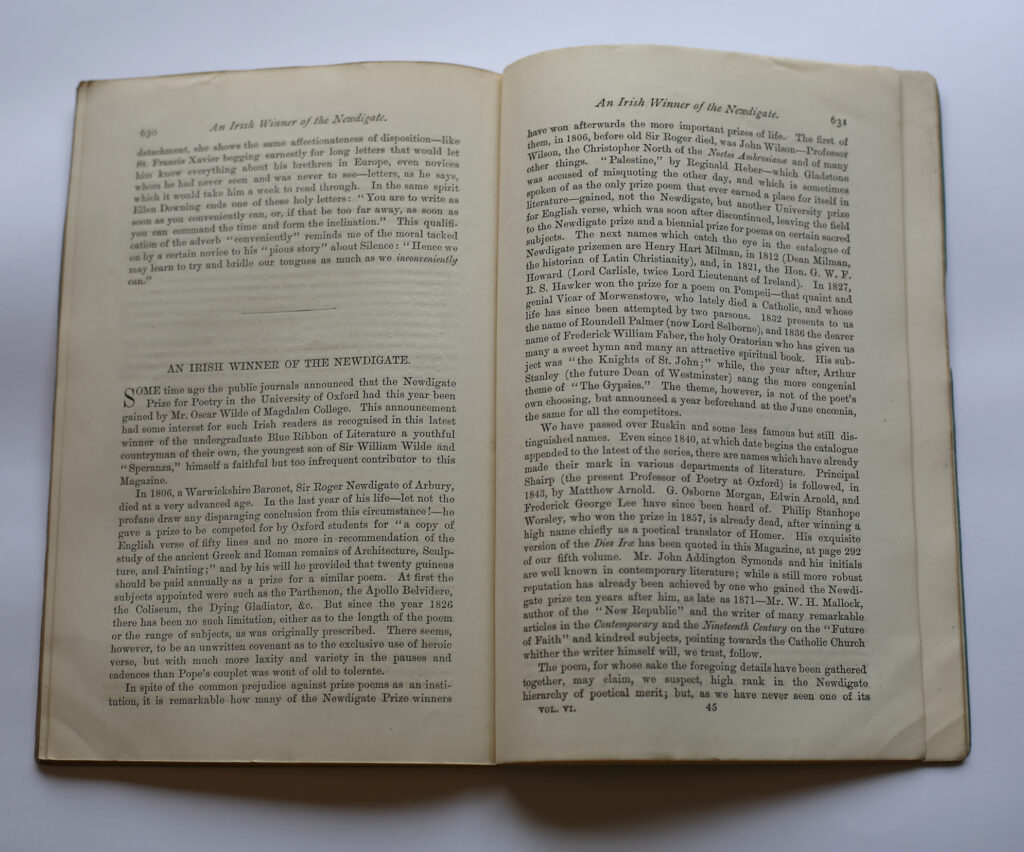

In 1878, his last year as an undergraduate, Wilde won the University’s Newdigate English Verse Prize. The award conferred membership to an elite circle of men. Matthew Arnold, John Ruskin and John Addington Symonds were among previous winners. They were also among the cultural giants on whose shoulders Wilde hoped to stand, one day. “I should so like to see the smile on your face now,” his mother wrote from Dublin. The prize was widely publicised in the English-speaking world and especially in Ireland, where Wilde’s brother personally delivered the news to the Dublin papers. “To have snatched the English Verse prize at Oxford is not only a personal distinction,” an Irish friend congratulated him, “but a triumph for our entire country.”

O. Wilde, “An Irish winner of the Newdigate” in The Irish Monthly 6 (1878): 630, 33. Courtesy of the Master and Fellows of University College Oxford: Ross e.609.

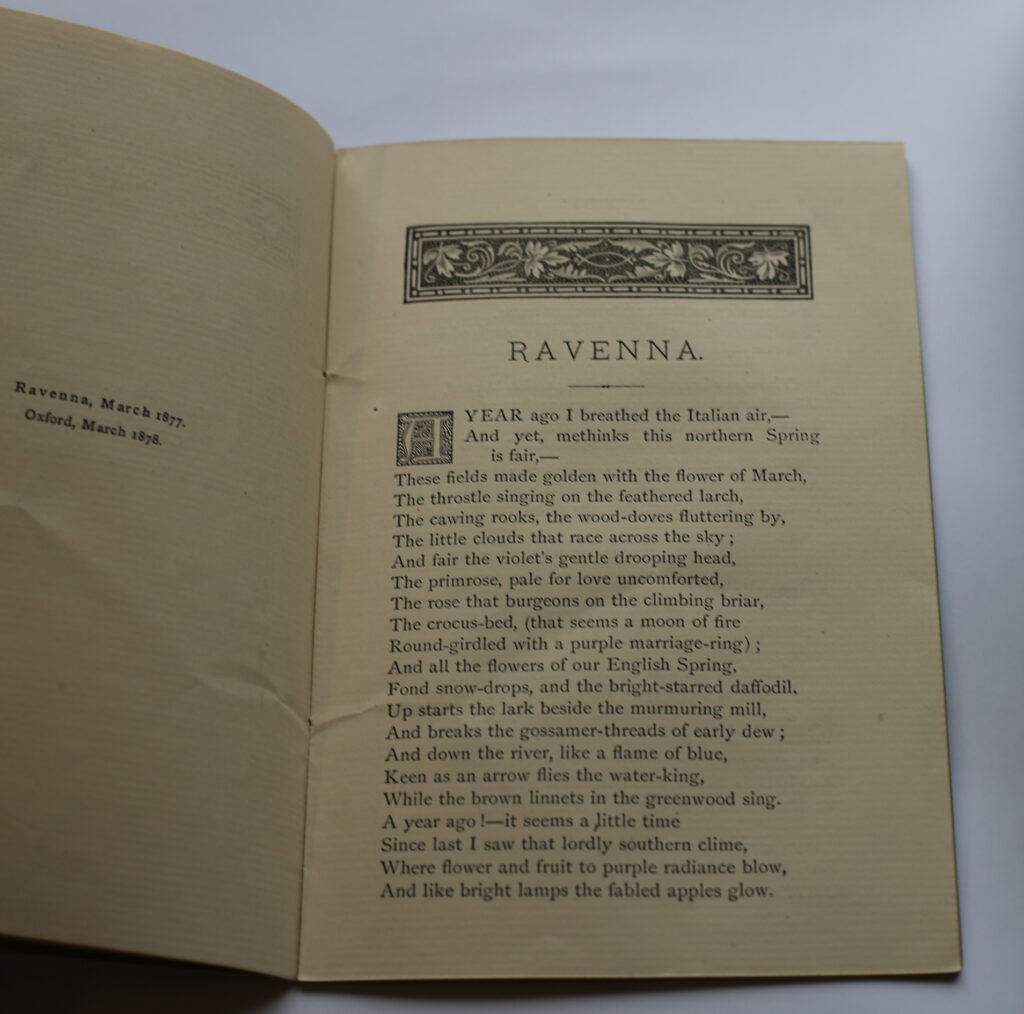

Wilde’s winning entry was “Ravenna,” a 332-line poem celebrating that city’s great citizens and its place in recently unified Italy. He said it sprang “from the bottom of my heart, red-hot from Ravenna itself.” By a stroke of luck, he had visited Ravenna while touring the Mediterranean the year before the Oxford University Gazette announced the topic of the competition.

Wilde’s poem canonizes an eclectic selection of English poets – Shelley, Shakespeare, Spencer and Byron, but also Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Critically acclaimed during her lifetime, Barrett Browning’s inclusion is a clue to Wilde’s nonconformist cast of mind. His interest in women’s writing continued into his later life, when he edited The Woman’s World magazine and reformed it to make it more progressive.

O. Wilde, Ravenna: recited at the Theatre, Oxford, June 26, 1878 (Oxford: Shrimpton and Son, 1878)

Courtesy of the Master and Fellows of University College Oxford: Ross e.85.

Shortly before Wilde’s graduation, Col. Thomas Wentworth Higginson arrived in Oxford. “It is lovely here,” the distinguished American author and Civil War veteran wrote, admiring the “perfect June weather.”

At Commemoration, in 1878, black-gowned students, dons and red-robed honourees processed in swishing gowns – “men only” the Colonel observed. Soon Wilde was called to the podium. Dressed in a sober graduand’s gown, he disclaimed “Ravenna” from memory and was loudly cheered. It was the culmination of his Oxford career, and a personal triumph.

To our visiting American observer, however, Wilde’s recital of “Ravenna” didn’t seem noteworthy. Instead, Col. Higginson found himself captivated by a striking young man he described as “a very black youth from Africa” whom he saw conspicuously floating among the cream of English manhood in a B.A. gown. ”King Cole,” a royal name that testified to his celebrity, was the name that Higginson heard the undergraduates call him.

Three cheers for Christian Cole! students shouted as he entered the theatre.

T. Shrimpton, ‘Old King Cole’ from 1224 caricatures of Oxford life.

Reproduced by kind permission of The Bodleian Libraries, The University of Oxford: G.A. Oxon 4o 414, fol. 533.

History was repeating itself. Once again, Christian Cole had stolen the show. Cole was still a familiar presence in Oxford. Following his graduation, he returned briefly to Sierra Leone and published lectures on education, but was now back in England seeking better prospects.

Wilde left Oxford with his artistic credentials burnished by the Newdigate Prize and his intellectual reputation gilded by a double First in Literae Humaniores, an outstanding academic result. “The dons are ‘astonished’ beyond words,” he said, about “the Bad Boy doing so well in the end!”.